本篇是 Adam B Kashlak 老师的 Probability and Measure Theory 课程笔记 Part 3

Probability Theory

Spaces

SpaceLet be a measure space and a measurable function, then we say , for if

For , we say if

This definition allows us to write down the norm, which is defined as:

Markov / Chebyshev and Jensen’s Inequalities

Markov’s InequalityLet f be a non-negative measurable function and . Then, denote ,

ProofNoting that , then by monotonicity of the integral,

which proves the theorem.

There are two useful ways to use Markov’s inequality:

- Chebyshev’s Inequality: For measurable and ,

- Chernoff’s Inequality: For measurable and , In probability theory, the right hand side becomes the moment generating function or the Laplace transform.

Convex Functions onLet be an interval. A function is convex if for all and all ,

Let be a probability space and an integrable random variable ( i.e. a measurable function in ) such that . For any convex ,

which is

ProofFor some , if , -a.e., then the result is immediate. Otherwise, let be the mean of , which lies in the interior of interval. Then, we can choose such that for all with equality at . Then, , and

Lastly, to check that is well defined (i.e. not ), we note that where is concave and . Hence, .

Hölder and Minkowski’s Inequalities

Hölder’s InequalityLet be conjugate indices ( i.e. ) and and be measurable, then

ProofIf either or , then the result is immediate. Hence, for such that , we can normalize and without loss of generality assume that . Then, we can define a probability measure on such that for any ,

Then, using Jensen’s Inequality with and ,

From Hölder’s inequality with , we can derive Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality:

Cauchy-Schwarz InequalityFor measurable and ,

Let and , be measurable functions, then

ProofIf either or or , then we are done. If , then and the result follows quickly. For and conjugates, we note that

Then using the above equality, we have

Divide both sides by finishes the proof.

Approximation TheoremLet ) be a measure space, and let be a -system such that and for all and there exists . Let the collection of simple functions be

For and for all and all , there exists a such that .

ProofFor any . Thus for all . Since is a linear space, .

Next, let be all that can be approximated as above by some and . Let be approximated by then by Minkowski’s Inequality,

Hence, is also a linear space.

Now, assume ( i.e. ). Let , which we will show is, in fact, a -system. We know that and thus . For such that then since is linear, so . Lastly, for pairwise disjoint with , let and . Then, and . Therefore, , and thus is a -system. By Dynkin - Theorem, and thus for any . Therefore, for any non-negative , we can construct simple functions such that . Then pointwise and . Hence, by Dominated Convergence Theorem, . Thus and by the linearity of , .

Lastly, for general , we have by assumption a sequence . Hence, for any , we have that and similarly to above, pointwise and . Therefore, by dominiated convergence. Thus, .

Convergence in Probability & Measure

Convergence of Measure

Weak Convergence of MeasureLet be a metric space and be the Borel -Field on . Then, for a measure and a sequence , we say that converges weakly to , i.e. , if

for all , all continuous bounded real-valued functions on .

For and on a metric space , the following are equivalent:

- for all bounded uniformly continuous functions

- for all closed sets

- for all open sets

- for all sets with

Proof

(1)(2) If convergence holds for every then is certainly hold for all bounded uniformly continous .

(2)(3) For any closed and there exists a such that for , we have as as . Then, we can define an such that on , on . Then is uniformly continuous (by Urysohn’s Lemma) and Then, by (2), we have that

Thus, taking the and to zero gives

(3)(1) Let . Our goal is to show that and similarly for to show (1) holds. As is bounded, we can shift and scale it, and without loss of generality, we assume that . Then, for any choice of , we define nested closed sets for all and cut into pieces to get

Also, , the above becomes

Thus,

Taking gives . Replacing with gives . Thus the and coincide proving that (3)(1).

(3)(4) Let be the complement of . Then, Thus, is equivalent to .

(3)(4)(5) For any set with , is an open set and is a closed set. If (3) and (4) hold, we have that

Since , we have that . This is equivalent to , which is (5).

Convergence of Random Variables

In contrast to convergence of measures, let be a probability space and be a metric space with Borel sets as above. Then, for a random variable (i.e. measurable function) , we can define a probability measure

This is the distribution of . Then the expectation of a random variable can be written in multiple ways due to change of variables:

Note that above Portmanteau Theorem can be rephrased for random variables as well.

Convergence in DistributionFor a sequence of random variables , we say that converges to in distribution ( denoted ) if .

Convergence in ProbabilityFor a sequence of random variables , we say that converges to in probabilty ( denoted ) if for all

In short, .

This means that the measure of the set of where and differ by more than goes to zero as . Convergence in probability is closely connected to the metric on .

Convergence Almost SurelyFor a sequence of random variables , we say that converges almost surely to ( denoted ) if

i.e. pointwise convergence almost everywhere.

Convergence inFor a sequence of random variables , we say that converges to in if

Here, we can think of as a function from to . In the case that we have real valued random variables, i.e. , then this is

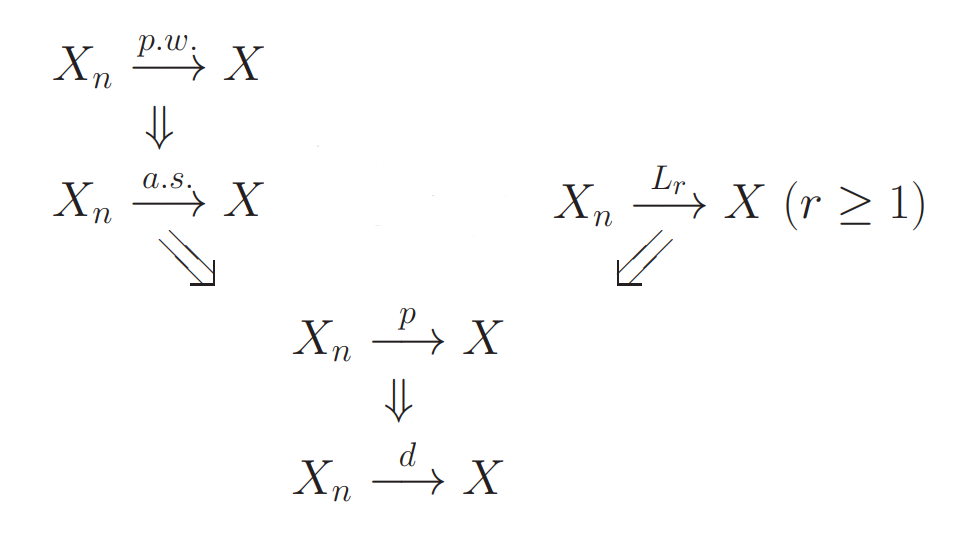

Hierarchy of Convergence Types

- Conv a.s. conv in probability

- Conv in probability conv in distribution

- For , conv in conv in

- For any , conv in conv in probability

Borel-Cantelli Lemmas

Let be a probability space. For , then we define

The set is sometimes referred to as infinitely often or i.o. This is because implies that for any there exists an such that . Similarly, some write eventually or ev. for . This is because for then there exists an large enough such that for all .

Let with . If , then .

ProofAs the summation converges, then the tail sum has to tend to zero, we have simply that

as .

Let be an independent collection with . If , then .

ProofNote that for all and we have that the independence of the implies the independence . Therefore, for any and ,

Taking takes the right hand side to zero. Hence, for all . Thus,

which is the desired result.

Law of Large Numbers

Let be random variables from to . Hence, for any , we write

and . Furthermore, we define the partial sum , which is also a measurable random variable.

IndependenceFor random variables and on the same probability space but possibly with different codomains, and respectively, we say that and are independent if

for all and .

This definition can be extended to a finite collection of random variables implying

for all . We say that an infinite collection of random variables is independent if all finite collections are independent.

Note that since is shorthand for , random variables and are independent if and only if the -fields and are independent ( defined in here ).

Identically DistributedFor , the distribution of is the measure induced by on , i.e., for . We say that and are identically distributed if and coincide almost surely.

Weak Law of Large Numbers

Weak Law of Large NumbersLet be a probability space and be random variables (measurable functions) from to such that and for all and for all . Then .

ProofWithout loss of generality, we assume . Otherwise, we can replace with . Then, for any , Chebyshev’s inequality implies that

as .

Note that in the above proof, we only require that the be uncorrelated (i.e. ) and not independent. In the next theorem, we require independence, but remove all second moment conditions.

Strong Law of Large Numbers

Strong Law of Large NumbersLet be i.i.d. random variables from to .

- If , then does not converge to any finite value.

- If , then for .

Proof

Assume that but also that , and note that . Since , then and 2nd Borel-Cantelli Lemma says that for infinitely many . Thus

Thus .

Assume that . Without loss of generality, we assume for all . Otherwise, we can write and independence of and implies independence for and . Also, we use to denote the distribution of , i.e. .

We define and . For any , we can define a non-decreasing integer sequence . Then and . Therefore,

for some constant . We also note that . By Chebyshev’s inequality, , depending on and such that

And thus . Hence, by 1st Borel-Cantelli Lemma, . Since , we have that and in turn that .

To get back to and , we note that if and only if . Thus and 21stnd Borel-Cantelli Lemma says that so for large enough, a.s. We define “large enough” to be ( i.e. ) Furthermore, and as , meaning that the contribution of the terms where and may not coincide becomes negligible. Hence, , so we have almost sure convergence of a subsequence.

Finally, since , there exists an large enough such that . Thus, for ,

Thus, taking concludes the proof.

Central Limit Theorem

Gaussian Measure onA Borel measure on is said to be Gaussian with mean and variance if

Gaussian Measure onA Borel measure on is said to be Gaussian if for all linear functionals , the induced measure on is Gaussian.

Gaussian Random VariableA random variable from a probability space to is said to be Gaussian if is a Gaussian measure on.

Characteristic FunctionFor a probability measure on , the characteristic function (Fourier transform) : \mathbb{R}^d \rightarrow \mathbb{C}$ is defined as

We can also invert the above transformation. That is, if is integrable with respect to Lebesgue measure on , then

ConvolutionFor two measures and on , the convolution measure is defined as

for all where .

Note that the convolution operator is commutative and associative. Also, for two independent random variables and with corresponding measures and , the measure of is .

Uniquesness of Characteristic Function TheoremLet and be probability measures on . If then .

ProofLet be a mean zero Gaussian measure on with variance . We denote and similarly for . It can be shown that the corresponding density functions for and are

Since , we have that for all .

Let be a random variable corresponding to and to . Then, the measure is paired with the random variable . Thus as , that is, pointwise for almost all . Thus, this convergence holds in probability and thus in distribution, i.e as .

Lastly, we have that and . Since the limit is unique .

Central Limit TheoremLet be a probability space, be i.i.d. random variables on such that and . Let . Then, where is a gaussian random variable with zero mean and covariance with th entry .

ProofAs the random vectors are mean zero and independent for . In turn, for any ,

For any , there exists an such that . Thus, from Chebyshev’s inequality, we have that . This implies that the sequence is “uniformly tight.

For a vector , the random variables are i.i.d. real-valued with and . Let be the characteristic function of .Then, and and Thus, by Taylor’s Theorem, we have

Thus, for any fixed vector ,

as . Thus, by the Uniqueness of Characteristic Function Theorem, we have that where is a Gaussian random variable with zero mean and covariance .

Erogodic Theorem

Measure Preserving MapLet be a measure space. A mapping is called measure preserving if

Invariant Set and FunctionFor a mapping ,

A set is -invariant if . The set of all -invariant sets forms a -field .

A measurable function is -invariant if . is -invariant if and only if is -measurable, i.e.

Ergodic MapA mapping is said to be ergodic if for any ,

Example

For Lebesgue measure on , two examples of measure preserving maps are the shift map

and Baker’s Map

Furthermore, it can be shown that

- If is integrable and is measure preserving then is integrable and

- If is ergodic and is invariant, then -a.e. for some constant .

Birkhoff and von Neumann’s Theorems

In what follows, we let be a measure space, be a measure preserving transformation, a measurable function, and

where .

Maximal Ergodic LemmaLet be integrable and = (element-wise maximum). Then,

ProofLet and . Then, for ,

Furthermore, on the set ,

On the set , since and we have that Thus, integrating both sides of the above gives

Since is integrable and is measure preserving, . Thus, we have . As , we have that

due to Dominated Convergencee Theorem with as the dominating function.

Let be a -finite measure space and . Then, there exists an -invariant such that

and as -a.e.

ProofBoth and are -invariant. Indeed, Thus, we can define a set for

which means that the and are separated, and this set is -invariant. The goal of the proof is to show that . Without loss of generality, we take . Otherwise, and we multiply everything by .

For some such that , then we set . Function is integrable and for each , there is an such that since . Thus, and the Maximal Ergodic Lemma says that

As is -finite, there exist such a sequence of sets such that and for all . Thus,

This implies that . Redoing the above argument for and results in . Therefore,

and since , we have that .

Next, let

Then, is -invariant as the and are. Furthermore, . Thus, .

This means that converges in on . Therefore, we define

Lastly, ( is measure preserving )and thus for all . Applying Fatou’s Lemma gives

finishing the proof.

Let and . Then, for all , there exists an such that and

Proof

We begin by noting that

By the above and the Minkowski’s Inequality, . Since , given a , we can choose a such that with

i.e. is bounded above and below by and . By the Birkhoff Ergodic Theorem, -a.e.

Next, we note that for all , and thus by (Dominated Convergence Theorem)[#dominated-convergence-theorem], there exists an such that for all ,

Applying Fatou’s Lemma gives that

Thus, for ,

Since , the convergence must hold in as well. Thus, we have

which gives the desired result.

Law of Large Numbers, Again

Let (Ω, F, P) be a probability space with i.i.d. real-valued random variables with distribution function . We define a map by

Let be the corresponding probability measure on .

Because the variables are independent, has the form , and because they are identically distributed, all the marginal distributions are the same, so in fact for some probability distribution on .

For a sequence , we can define the shift map to be

Then the shift map is measure preserving and ergodic by Kolmogorov’s zero-one law.

Strong Law of Large Numbers, AgainLet be i.i.d. random variables from to . If , then for .

Proof

Let by taking the first coordinate, that is, for , . Then, for being the shift map and , we have

Thus, von Neumann’s Ergodic Theorem says that there exists an invariant such that

for and

Since is ergodic, the result from the beginning of this section states that , a constant, almost surely. Thus,

gives the disred result.